Easter and Hocktide

Up-date April 2021 and 2023

Where did Easter come from?

Does the following sound familiar?

Spring is in the air! Flowers and bunnies decorate the home. Father helps the children paint beautiful designs on eggs dyed in various colors. These eggs, which will later be hidden and searched for, are placed into lovely, seasonal baskets. The wonderful aroma of the hot cross buns mother is baking in the oven waft through the house. Forty days of abstaining from special foods will finally end the next day. The whole family picks out their Sunday best to wear to the next morning’s sunrise worship service to celebrate the Savior’s resurrection and the renewal of life.

Everyone looks forward to a succulent ham with all the trimmings. It will be a thrilling day. After all, it is one of the most important religious holidays of the year. Easter, right? No!

This is a description of an ancient Babylonian family - 2,000 years before Christ - honouring the resurrection of their god, Tammuz, who was brought back from the underworld by his mother/wife, Ishtar (after whom the festival was named). As Ishtar was actually pronounced “Easter” in most Semitic dialects, it could be said that the event portrayed here is, in a sense, Easter. Of course, the occasion could easily have been a Phrygian family honouring Attis and Cybele, or perhaps a Phoenician family worshipping Adonis and Astarte. Also fitting the description well would be a heretic Israelite family honoring the Canaanite Baal and Ashtoreth. Or this depiction could just as easily represent any number of other immoral, pagan fertility celebrations of death and resurrection - including the modern Easter celebration as it has come to us through the Anglo-Saxon fertility rites of the goddess Eostre or Ostara. These are all the same festivals, separated only by time and culture.

Written by Anne on 15th April 2019

Easter

The Anglo Saxons called April ēastre-monaþ. The Venerable Bede says in The Reckoning of Time that this month, ēastre, is the root of the word Easter. He further states that the month was named after a goddess Eostre whose feast was in that month. This is also attested by Einhard in his work, Vita Karoli Magni.

Jacob Grimm wrote in his 1835 Teutonic Mythology:

“Ostara, Eástre, seems therefore to have been the divinity of the radiant dawn, of up springing light, a spectacle that brings joy and blessing, whose meaning could be easily adapted by the resurrection-day of the Christian’s God.“

He dismissed the idea that Bede could have invented Ostara, writing of these ancient Teutonic goddesses:

“there is nothing improbable in them, nay the first of them is justified by clear traces in the vocabularies of Germanic tribes.”

Grimm also wrote that the white maiden of Oster was said to appear with a bunch of keys on Easter morning, when she would stride to the brook to collect water – because water drawn on Easter morning is holy and healing.

So, Eostre is considered the Germanic Goddess of Spring. Also called Ostara or Eastre, She gave her name to the Christian festival of Easter whose timing is still dictated by the Moon. Some modern pagans celebrate her festival on the Vernal Equinox, usually around March 21, the first day of Spring.

Eostre is connected with renewal and fertility. Eggs and rabbits are sacred to her, as is the full moon, and if you look closely at the moon you can see the image of a rabbit or hare.

She is also a dawn goddess, and may be related to the Greek Goddess of the dawn, Eos.

THE EASTER EGG

The egg is an ancient symbol of new life and has been associated with pagan festivals celebrating spring. Eggs as a symbol of fertility and abundance may stretch back to the goddess-worshipping cultures of the Neolithic!

The decoration of eggs is believed to date back to at least the 13th century. One explanation for this custom is that eggs were formerly a forbidden food during the Lenten season, so people would paint and decorate them to mark the end of the period of penance and fasting, then eat them on Easter as a celebration.

In the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, Easter eggs are dyed red to represent the blood of Christ, with further symbolism being found in the hard shell of the egg symbolizing the sealed Tomb of Christ - the cracking of which symbolized his resurrection from the dead.

In the 17th and 18th centuries egg-shaped toys started to be made and given to children at Easter. The Victorians had cardboard, 'plush' and satin covered eggs filled with Easter gifts and chocolates. Carl Fabergé made the ultimate fabulous jewelled egg-shaped Easter creations, during the19th century, for the Russian Czar and Czarina, which are now precious museum pieces.

Chocolate Easter eggs were first made in Europe in the early 19th century, with France and Germany taking the lead in this new artistic confectionery. Some early eggs were solid, as the technique for mass-producing moulded chocolate had not been devised.

John Cadbury made his first Easter Eggs in 1875. Progress in the chocolate Easter egg market was slow until a method was found for making the chocolate flow into the moulds.

The earliest Cadbury chocolate eggs were made of 'dark' chocolate with a plain smooth surface and were filled with sugared almonds. The earliest 'decorated eggs' were plain shells enhanced by chocolate piping and marzipan flowers.

An Egg Hunt is a game during which Easter Eggs are hidden for children to find. Real hard-boiled eggs, which are typically dyed or painted, artificial eggs made of plastic filled with sweets or foil-wrapped egg-shaped chocolates of different sizes, are hidden in various places. The game is often played outdoors, but can also be played indoors. The children typically collect the eggs in a basket and there’s a prize for whoever collects the most eggs.

Egg Rolling is also a traditional Easter egg game. In the United Kingdom, Germany, and other countries children traditionally rolled eggs down hillsides at Easter. This tradition was taken to America by European settlers.

Casscarones, is a Latin American tradition, now shared by many US States, when emptied and dried chicken eggs are stuffed with confetti and sealed with a piece of tissue paper. The eggs are hidden in a similar tradition to the Easter Egg Hunt and when found the children (and adults ) break them over each other's heads for luck.

Easter fountains

This reminds me of the well-dressing custom in Derbyshire, England, where flowers and natural objects are used to decorate the town wells. And in Ireland the annual cleaning of the holy well with salt. NJ.

More information here from By Ms. Bianca Sowders at the army.mil website

Many communities, especially in Franconia, decorate their fountains and village wells with Easter wreaths, decorations and eggs. A lot of them can be found in the Fränkische Schweiz (Franconian Switzerland), which extends roughly between the cities of Bamberg, Forchheim and Bayreuth. Examples for villages with decorated fountains are Bieberbach, which lays claim to featuring the largest of them all, Birkenreuth in Wiesenthal or Haag (part of Aufsess), which has been decorating fountains for Easter for more than 100 years.

There was an old tradition throughout Germany of drawing water in silence at Easter for purification and medical treatment, which was sometimes referred to as Osterbrunnen. Wells were cleaned and decorated with garlands and sometimes eggs in May, a tradition which survived relatively late in the 19th century in Bacharach. Other dates for well decorating included Pentecost in southern Thuringia and Midsummer in Fulda; it took place at Easter in Bohemia. Nineteenth-century writers, particularly Karl Weinhold, suggested that these traditions of well cleaning and decorating were remnants of pre-Christian practices.

THE EASTER BUNNY

Originating among German Lutherans, the "Easter Hare" originally played the role of a judge, evaluating whether children were good or disobedient in behaviour at the start of the season of Eastertide. The Easter Bunny is sometimes depicted with clothes. In legend, the creature carries coloured eggs in his basket.

The EncyclopediaMythica says that:

Ostara is the personification of the rising sun. In that capacity she is associated with the spring and is considered a fertility goddess. She is the friend of all children and to amuse them she changed her pet bird into a rabbit. This rabbit brought forth brightly coloured eggs, which the Greek goddess gave to children as gifts. From her name and rites the festival of Easter is derived.

In his 1835 book Deutsche Mythologie, Jacob Grimm states that

“the Easter Hare is unintelligible to me, but probably the hare was the sacred animal of Ostara … ”

The earliest reference to an egg-toting Easter Bunny can be found in a late 16th-century German text (1572).

“Do not worry if the Easter Bunny escapes you; should we miss his eggs, we will cook the nest.”

A century later, a German text once again mentions the Easter Bunny, describing it as an “old fable”, and suggesting that the story had been around for a while before the book was written.

I love the following tale....

| The Goddess Ostara and the Easter Bunn |  |

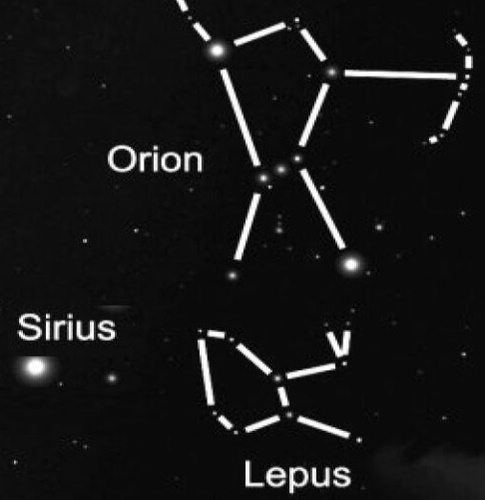

Already feeling just a little bit guilty for arriving late one spring, the Goddess Ostara was appalled when the first thing she encountered was a little bird who lay dying on the forest floor, his wings frozen by the snow. Filled with compassion, Ostara took him as a pet or, as some versions of the tale have it, her lover. Feeling sorry that the poor wingless bird could no longer take flight, she turned him into a snow hare and gave him the ability to run rapidly so he could evade all hunters. Honouring his earlier life as a bird, she also gave him the ability to lay eggs in all the colours of the rainbow. Whatever could the goddess Ostara been thinking when she turned him into a randy rabbit? Eventually the decision backfired when the goddess became enraged with his numerous affairs. In a fit of anger, she threw him into the skies where he unfortunately landed under the feet of the constellation Orion (the Hunter). He remains there to this day, and is known to us as the constellation Lepus (The Hare). Softening her attitude a bit, Ostara allowed the hare to return to earth once each year to give away his coloured eggs to the children attending the Ostara festivals that were held each spring. The tradition of the Easter Bunny had thus begun. |

Easter and it’s traditions serve to remind us of the cycle of rebirth and the need for renewal in our lives. In the history of Easter, Christian and pagan traditions are delicately interwoven with grace and beauty.

So have a happy Easter and don’t eat too many chocolate eggs!

Hocktide

Hocktide is a two-week long period following Easter.

The most well-known day is Tutti-Day (also known as Hock Tuesday or Hockney Day), and the chief event of Tutti-Day is the holding of the Hocktide Court. There are a number of other functions and events that take place through the fortnight, including Ale Tasting and the Commoners' Luncheon.

It was an English medieval festival; both the Tuesday and the preceding Monday were the Hock-days. Together with Whitsuntide and the twelve days of Yuletide these marked the only holidays of the farmer's year.

At Coventry there was a play called The Old Coventry Play of Hock Tuesday. This, suppressed during the Reformation because of the disorder that accompanied it, it was revived as part of the festivities of Queen Elizabeth's visit to Kenilworth in July 1575. The play depicted the struggle between Saxons and Danes, and has given colour to the suggestion that Hocktide was originally a commemoration of the massacre of the Danes on St.Brice's Day, 13 November 1002, or of the rejoicings at the death of Harthacanute on 8 June 1042 and the expulsion of the Danes. But the dates of these anniversaries do not bear this out.

In England as of 2017 the tradition survives only in Hungerford in Berkshire, although the festival was somewhat modified to celebrate the patronage of the Duchy of Lancaster. John of Gaunt, the 1st Duke of Lancaster, granted grazing rights and permission to fish in the River Kennet to the commoners of Hungerford. Despite a legal battle during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) when the Duchy attempted to regain the lucrative fishing rights, the case was eventually settled in the townspeople's favour after the Queen herself interceded. Hocktide in Hungerford now combines the ceremonial collecting of the rents with something of the previous tradition of demanding kisses or money.

The Hocktide Council, which is elected on the previous Friday, appoints two Tutti Men whose job it is to visit the properties attracting Commoner's Rights. Formerly they collected rents, and they accompanied the Bellman (or Town Crier) to summon commoners to attend the Hocktide Court in the Town Hall, and to fine those who were unable to attend one penny, in lieu of the loss of their rights.

The Tutti Men carry Tutti Poles: wooden staffs topped with bunches of flowers and a cloved orange. These are thought to have derived from nosegays which would have mitigated the smell of some of the less salubrious parts of the town in times past.

The Tutti Men are accompanied by the Orange Scrambler- who wears a hat decorated with feathers and carries a white sack filled with oranges - and Tutti Wenches who give out oranges and sweets to the crowds in return for pennies or kisses.

The proceedings start at 8 am with the sounding of the horn from the Town Hall steps. This summons all the commoners to the attend the Court at 9 am, after which the Tutti Men visit each of the 102 houses in turn. They no longer collect rents, but demand a penny or a kiss from the lady of the house when they visit. In return the Orange Man gives the owner an orange.

After the parade of the Tutti Men through the streets the Hocktide Lunch takes place for the Hocktide Council, commoners and guests, at which the traditional "Plantagenet Punch" is served. After the meal, an initiation ceremony, known as Shoeing the Colts is held, in which all first-time attendees are shod by the blacksmith. Their legs are held and a nail is driven into their shoe. They are not released until they shout "Punch". Oranges and heated coins are then thrown from the Town Hall steps to the children gathered outside.